Fruit drink labeling is confusing to many parents, study finds

In the research, nearly seven in 10 parents were confident or very confident they could identify added sugars. When looking at only the front of packages, 84% were able to correctly identify these products. While research found that parents who viewed Nutrition Facts and ingredients information on drink packaging were more likely to call out the products with sugar and diet sweeteners, this information alone was not enough to help the one-quarter of parents who thought sweetened flavored waters had no added sugar.Health experts have roundly cautioned parents to limit their kids’ sugar and sweetener consumption. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends young children not consume sugary drinks or products that contain diet sweeteners. U.S. Dietary Guidelines also advise against these products for children under age 2. Studies have tied sugar consumption to obesity, diabetes and high blood pressure. But 25% of 1- to 2-year-olds and 45% percent of 2- to 4-year-olds consume sugary beverages on any given day, the report notes.Manufacturers have attempted to respond to parents’ concerns about the sugar content in children’s juices, with new products rolling out from Juicy Juice, Honest Tea and Hint. Juice waters are another recent innovation. In 2020, Nestlé Pure Life introduced a Fruity Water line with no sugar or sweeteners. And early this year, PepsiCo debuted a line of juice waters for teens with no added sugar or artificial sweeteners. This category of beverages causes its own level of confusion. Parents in the Rudd Center research were more likely to believe statements such as “natural” and “water beverage” on packaging meant the beverage had no added sugar or diet sweeteners and contained juice, even though the opposite could be true. However, many parents clearly feel underequipped to evaluate the suitability of children’s drinks or decipher ingredient listings. For example, according to the Rudd Center research, less than half of parents felt they could identify diet sweeteners. T

no added sugar or artificial sweeteners. This category of beverages causes its own level of confusion. Parents in the Rudd Center research were more likely to believe statements such as “natural” and “water beverage” on packaging meant the beverage had no added sugar or diet sweeteners and contained juice, even though the opposite could be true. However, many parents clearly feel underequipped to evaluate the suitability of children’s drinks or decipher ingredient listings. For example, according to the Rudd Center research, less than half of parents felt they could identify diet sweeteners. T his category includes sucralose and acesulfame K — names that could be foreign to many consumers who are readin

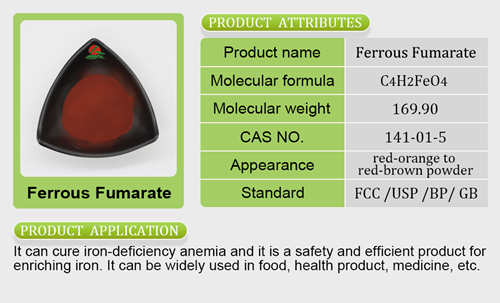

his category includes sucralose and acesulfame K — names that could be foreign to many consumers who are readin g an ingredient list. According to 2020 research from the Sugar Association, 63% of consumers were unable to identify sugar substitutes amagnesium glycinate puritan’s prides the sweetening ingredient in foods. And two-thirds felt that food companies should be required to clearly identify sugar substitutes as “sweeteners” in ingredient lists. The FDA has been weighing how to label added sweeteners in food, such as maltitol, rebaudioside A and erythritol. The Sugar Association has argued that currently, manufacturers can label products with such ingredients as “no sugar added,” which leads some magnesium malate food sourcesconsumers to assume the products have no other sweetthorne cal mageners. The recent research seems to corroborate how much the terminology around sweeteners is confusing to consumers, and parents in particular. Researchers with the University ofcyanocobalamin ferrous fumarate and folic acid capsules uses Connecticut and New York University

g an ingredient list. According to 2020 research from the Sugar Association, 63% of consumers were unable to identify sugar substitutes amagnesium glycinate puritan’s prides the sweetening ingredient in foods. And two-thirds felt that food companies should be required to clearly identify sugar substitutes as “sweeteners” in ingredient lists. The FDA has been weighing how to label added sweeteners in food, such as maltitol, rebaudioside A and erythritol. The Sugar Association has argued that currently, manufacturers can label products with such ingredients as “no sugar added,” which leads some magnesium malate food sourcesconsumers to assume the products have no other sweetthorne cal mageners. The recent research seems to corroborate how much the terminology around sweeteners is confusing to consumers, and parents in particular. Researchers with the University ofcyanocobalamin ferrous fumarate and folic acid capsules uses Connecticut and New York University argue their findings underline the need for rferrous gluconate near meegulations that would require manufacturers to clearly note any added sugar, diet sweetener and juice content on the

argue their findings underline the need for rferrous gluconate near meegulations that would require manufacturers to clearly note any added sugar, diet sweetener and juice content on the front of children’s drink packaging, where parents are more likely to see it.

front of children’s drink packaging, where parents are more likely to see it.

Leave a Reply